July 12, 1979. A warm Thursday night at Chicago's Comiskey Park, where the hometown White Sox were scheduled to play a twi-night doubleheader against the Detroit Tigers. Although both teams were struggling through losing seasons and lacking any marquee stars, more records were broken that night than on any other date in baseball history. They were also detonated, trampled, and burned.

It was Disco Demolition Night, a promotional event in which any fan bearing a disco album was admitted for a mere 98 cents. Between games, the records were ritualistically destroyed. Bad idea. With the possible exception of Cleveland's Ten-Cent Beer Night, Disco Demolition Night went down as one of the most ill-conceived promotions in the annals of sport.

By the summer of 1979, the national disco backlash was approaching critical mass; "Disco Sucks" was its unofficial rallying cry. Rock fans despised the genre and critics dismissed it as a commercial-driven fad, even as the Rolling Stones, Rod Stewart, Blondie, and other such acts embraced the style and scored crossover hits.

Originating from a largely gay, largely black dance culture, disco cut through racial lines and integrated diverse crowds in a communal, pan-sexual boogie. For these reasons it was as loved by its adherents as it was loathed by its detractors, most prominently, white male rock 'n' rollers.

Among them was Steve Dahl, morning deejay at Chicago rock station WDAI. When WDAI switched to an all-disco format in December 1978, Dahl was subsequently fired, only to be hired three months later by another Chicago rock station, WLUP. In addition to Dahl, "The Loop" also captured many of WDAI's former listeners, similarly disgusted with Saturday Night Fever, the Village People, "Funkytown," and so forth.

Dahl courted his discophobic listenership by taking their shared hatred to the airwaves and launching an all-out anti-disco crusade. His antics included smashing up a copy of Van McCoy's million-selling single "The Hustle" over the air, doing so just the morning after McCoy suddenly died of a heart attack.

On a broader scale, Dahl formed the "Insane Coho Lips Anti-Disco Army," an ad hoc group "dedicated to the eradication and elimination of the dreaded musical disease known as disco." At its peak, the ICLADA claimed 7,000 card-carrying members.

It just so happened that the sports commentator on Dahl's show was White Sox promotions director Mike Veeck, son of beloved Sox owner Bill Veeck. The elder Veeck was considered a promotional genius, credited for devising events like Bat Day and being the first owner to stitch players' surnames on the backs of their jerseys. The goofball showman also installed the famed exploding scoreboard at Comiskey Park, and once made the Sox play a game in short pants. Perhaps his most memorable publicity stunt was the time he sent a midget in to pinch-hit.

Veeck was always on the lookout for crazy new promotions, and between him, his son Mike, and Steve Dahl, the trio cooked up Disco Demolition Night. Apparently it occurred to none of them that records are fun to throw, capable of slicing through the air like Frisbees, only with much greater distance and velocity.

The big night arrived, and so did the fans. Comiskey Park usually attracted more of a blue-collar crowd than the relatively well-heeled clientele across town at the Cubs' Wrigley Field, and was reputed to have sold more beer per person than at any other big-league venue. On this night, the crowd appeared more like it came out to see Blue Öyster Cult than a ballgame.

Dahl's Anti-Disco Army showed up in full force: an invasion of drunken, stoned, longhaired teens sporting Sabbath and Zeppelin shirts, carrying the requisite records along with signs and banners emblazoned with the ubiquitous "Disco Sucks." (There were likely soldiers from the KISS Army as well.) Not surprisingly, trouble arose before the first pitch was thrown.

Comiskey Park's 1979 capacity was listed at 44,492, though Sox officials estimated the overflow audience at 55,000. Another 20,000 were turned away when the gates closed, and police blocked exit ramps from the nearby interstate to keep even more fans from pouring into the area. Despite the beefed-up police presence, some of those locked out began climbing the stadium's two-story chain-link fences. Others simply rushed the turnstiles.

"We were trying to hold the main gate closed but the kids forced it open," explained one security guard. "The ushers got beat up."

Nevertheless, the first game started at 5:30, just as the records started to fly. Fans hurled discs around the stands and onto the field, showering the ballpark in a hail of vinyl. The players were both angry and nervous about having to compete under the constant bombardment of not only records, but also album covers, fireworks, beer cups, hot dogs, and anything else on hand. Batboys and groundskeepers periodically ran onto the field to clear the debris, which only further incited the crowd.

On the prospect of getting nailed by a Peaches and Herb LP, Detroit reliever Aurelio Lopez refused to warm up in the bullpen. Sox outfielder Wayne Nordhagen later complained, "How'd you like to get hit in the eye with one of those? These people don't realize it only takes one to ruin a guy's career."

Fortunately, no careers were ruined, and Detroit won the first game, 4-1. Game 2 was to begin a half-hour later.

During the intermission, a large wooden crate was placed in centerfield, filled with a few thousand disco records. Dahl emerged, wearing a green army helmet, and presided over some short ceremony. At its conclusion, Dahl detonated an explosive charge, which ignited several roman candle-type fireworks in front of the crate, and then the crate itself blew up. The crowd roared as cardstock sleeves and vinyl shards blasted into the air.

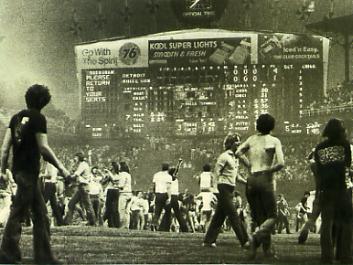

The salvo was a call-to-arms for fans to storm the field. At first, just a few guys sprung from the stands; before long, an estimated 7,000 hooligans were running amok, as if the Sox had won the pennant. A few players were warming up on the field as the chaos started, but then quickly bolted for the dugout. Some picked up bats.

Bonfires blazed as records continued to sail and fireworks continued to explode. The batting cage was torn down and dragged around the field while some guys scaled the yellow mesh foul line markers. One young man grabbed a high-powered hose and blasted water around the outfield, and others tore up the neatly manicured infield. Chunks of Kentucky bluegrass were ripped away, and much of what remained was scorched. Girls rode on the shoulders of their bare-chested boyfriends, while some kids just ran the bases. Bottles were thrown and fistfights broke out.

Those who waited in the stands for the second game chanted, "Clear the field!" Bill Veeck and Sox radio announcer Harry Caray made similar appeals over the PA system, yet the rioters were oblivious to their pleas. The scoreboard ineptly flashed: "Please Return to Your Seats."

Stadium security was overwhelmed, though the revelers eventually began to wear themselves out. Then, about half-hour after the disorder began, 80 riot-clad cops marched onto the field. Wearing blue helmets and armed with batons, the cops were greeted by cheers from the law-abiding fans who weren't part of the mob.

Most of the ruffians retreated to the stands upon mere sight of the infamous Chicago riot police, notorious for cracking skulls at the Democratic National Convention in '68. After clearing a few stragglers, the cops restored order within five minutes. Thirty-nine were arrested for disorderly conduct and spent the night in jail, and only a few minor injuries were reported.

The smoldering diamond resembled a battleground, strewn with refuse and missing sizeable patches of sod. Bill Veeck insisted the second game could still be played, but around 10 p.m., umpire Dave Phillips called it off.

Veeck immediately tried to reschedule the game on a later date, though Tiger manager Sparky Anderson demanded a forfeit: "The only thing that can force a postponement is an act of God. This was no act of God... The [condition of the] field is the responsibility of the home team. It's no different than a guy slipping on a banana peel in front of your house. You're at fault... Beer and baseball go together, and they have for years. But I think those kids were doing things other than beer."

The next day, American League president Lee MacPhail judged that the Sox had indeed forfeited the game, losing by a 9-0 score as dictated by the rulebook. Veeck slammed MacPhail's decision as "a grave miscarriage of justice," even as he accepted full blame for the fiasco: "Anything that happens here is my responsibility."

Veeck also criticized the rioters ("these weren't real baseball fans"), but took credit for restraining the police: "We used no force. We let 'em run until they got tired and bored. The worst injury we had all night was a guy who broke his ankle coming down a ramp."

In light of MacPhail's ruling, Sox manager Don Kessinger lamented, "We have found a lot of ways to lose games this year, but I guess we've added a new wrinkle. It's tough to lose two games when you played only one."

Sox pitcher Rich Wortham, a Texan who preferred the Grand Ole Opry to Grand Funk Railroad, blamed the music: "This wouldn't have happened if they had country and western night."

Possibly so. What was officially recorded as a Detroit twinbill sweep is better remembered as the zenith of the disco backlash. A few critics even viewed the album-torching and subsequent melee as a mass exercise in racism and homophobia, reminiscent of Nazi book-burnings. As one clueless 17-year-old rioter remarked, "This is our generation's cause."

The following month, Comiskey Park played host a rock festival featuring Foghat, the Beach Boys, the Tubes, and Sha Na Na. Once again the field was torn to shreds, causing the Sox to cancel another three games. The stadium itself was ultimately demolished in 1991, as the Sox moved across the street into "New Comiskey Park" (recently renamed "US Cellular Field"). Oddly enough, the Sox's bizarre tradition of on-field fan violence and subsequent arrests also followed the franchise to "The Cell": in 2002 a drunken father-son duo attacked Kansas City's elderly first base coach Tom Gamboa (he suffered permanent hearing damage); on a half-price ticket night in 2003, a fan accosted umpire Laz Diaz.

Bill Veeck, who eventually conceded that Disco Demolition Night was "a mistake," died in 1986 and was inducted into the Baseball Hall of Fame in 1991. Mike Veeck has since owned part of several minor league teams, and continues to dream up nutty promotions. He planned to give away free vasectomies during a Father's Day game, which he cancelled after a protest led by one of his season-ticket holders, a Catholic bishop. During the 2002 campaign he gave away seat cushions, each with baseball commissioner Bud Selig's mug printed on its surface.

As for Steve Dahl, who currently hosts an afternoon talk show on Chicago's WCKG, his army may have won the battle on Disco Demolition Night, but lost the musical war. Most of today's ballparks routinely blare disco-inspired music -- if not vintage disco tracks themselves -- replacing the traditional live organ with such staples as "More More More," "Boogie Shoes" and "Who Let the Dogs Out?".

However, Disco Demolition Night wasn't a complete failure, at least for one young woman in attendance. On the occasion of her first big-league ballgame, she exclaimed, "This is cool! Does it happen every night? I'll become a fan!"

All quotes are from the Chicago Tribune.

Originally appeared in issue #37 of the print zine Roctober, Winter 2003. Order it here.