Season in the Abyss

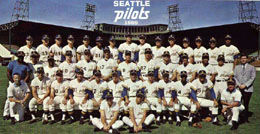

The 1969 Seattle Pilots

Go go you Pilots, you proud Seattle team

Go go you Pilots, go out and build a dream

You brought the Majors to the evergreen Northwest

Now go go you Pilots, you're go-ing to be the best!

-- "Go, Go You Pilots!" by Doris Doubleday and His Command Pilots (Pilotune Records, 1969)

Such cheery optimism greeted the Seattle Pilots in 1969, when the expansion team joined the American League as the Pacific Northwest's first Major League Baseball franchise. Just one miserable year later, the Pilots found themselves washed up, only to leave a mere footnote in the annals of sports history. The team didn't stick around long enough to make a lasting impression on hardly anyone; most of today's fans don't remember the ill-fated Pilots, if they've ever heard of them at all. There's little wonder why: in their lone season of existence, the Pilots fielded a lineup of rejects who played to a broken-down, largely empty minor league stadium. After losing nearly one hundred games, the incompetent owners declared bankruptcy. The team moved to another town and forged a new identity. America supposedly loves the underdog, but few gave a damn about the Pilots, who, as baseball briefly knew them, sank into oblivion.

Seattle had been a minor league city since the turn of the century, home to the Indians of the Pacific Coast League. Emil Sick, owner of the Rainier Brewery, purchased the team in 1938 and moved it into his brand-new ballpark at Rainier Avenue South and McClellan Street. Sick's Stadium held 15,000 in its grandstand, from which Mt. Rainier was visible beyond the outfield fence. The team was fittingly renamed the "Rainiers" and Seattle caught baseball fever, cheering them on to win seven PCL pennants over the next 30 years.

Despite its loyal support for the Rainiers, Seattle was pegged for expansion by Major League Baseball. This came to pass in December 1967, when the American League awarded Seattle a franchise to begin play in 1969. It seemed like a good idea at the time, as the Northwest market was viewed as an untapped goldmine. In a gesture of support, King County voters passed a bond measure in 1968 to fund a $40 million domed stadium for the new franchise to call home. But the team rushed itself into operation, and the venture quickly became a nightmare. From the get-go they were under-financed, and friction soon grew between the owners, city officials, and the league. While waiting for the domed venue to be built, old Sick's Stadium would serve as the temporary home of the newly-christened "Pilots." (The iffy nickname could've been worse, narrowly beating out "Green Sox" in a poll.) After thirty years of use, the antiquated facility, now owned by the city, required big-league renovations to properly accommodate a big-league team, including an expansion far beyond its relatively puny capacity. The upgrade began a mere three months before the start of the new season.

The Seattle Pilots made their Major League debut in Anaheim on April 8, 1969. Marty Pattin was credited with the win as they beat the California Angels, 4-3. Three days later, the Pilots took a 1-1 record into Seattle for the home opener against the Chicago White Sox. The interminable pre-game ceremonies included introductions of various honored guests -- baseball commissioner Bowie Kuhn, former Indian and Rainier stars, local politicians, Seattle police and fire chiefs and several others. Sportscaster Rod Belcher sang the Pilots' fight song/sea chanty, "Go, Go You Pilots!", which he composed, recorded, and released to local radio stations under the name "Doris Doubleday and His Command Pilots." By the time a reverend offered a prayer, the crowd had grown impatient with the lame pageantry. Meanwhile, the stadium upgrade was still in progress, even after the first pitch was thrown. Several hundred ticket-holders were forced to wait outside Sick's until the third inning, when their seats were finally hammered into place. The scoreboard had only been installed the night before and, without a proper flagpole, Old Glory hung from a light standard. Just 18,000 of the promised 25,420 seats were ready, which turned out to be plenty. On what might have been a truly historic day, just 17,150 turned. The Seattle Times put a bombastic spin on the scene, calling it "an arena unmatched in a century of baseball for a Major League spectacle." For the record, the Pilots shutout Chicago, 7-0. Pitcher Gary Bell was credited with the win, and first baseman Don Mincher hit a home run.

The rest of the seats were eventually installed, but the rickety stadium was in still in wretched condition and complaints mounted as the season progressed. Namely, it was ill-equipped to comfortably handle large crowds (that is, on the rare occasion one ever showed up). Most of the seats were splintered wooden benches, except for the box seats, which were folding metal chairs. Journalists groused that the press box wasn't air-conditioned, and since there were no field-level camera pits, photographers had to perch up high on the grandstand roof. The restrooms were often out of order because the facility had trouble with low water pressure, which almost disappeared when the attendance rose above 10,000. Because of unsanitary conditions, the players sometimes bypassed the locker rooms and went back to their hotels to shower.

The smattering of determined fans who could tolerate the decrepit environs had little to cheer about. The Pilot roster was mostly comprised of castoffs drafted from an expansion pool teeming with mediocre candidates, though a few players rose above marginal status. Don Mincher led the squad with 25 homers and also knocked in 78 runs, and was the Pilots' token representative at the All-Star Game. Left fielder Tommy Davis hit .271 and knocked in 80 runs (both team-bests), and speedy third baseman Tommy Harper topped the American League with 73 stolen bases. The leading pitchers were Gene Brabender (albeit with a 13-14 record), and the team's Most Valuable Player, Diego Segui (12-6, with a 3.36 ERA). Shortstop Ray Oyler batted a pitiful .165, yet had his own fan club organized by a smartass local disc jockey.

Adding insult to injury, the Pilots looked bad while losing, taking the field in bizarre, gaudy uniforms intended to reflect both Seattle's maritime and aeronautical traditions. The blue caps featured a gold "S" on the front with a gold underline, and a "scrambled eggs" design on the bill. The jerseys read "Pilots" in a weird lower-case, postmodern typeface, below the official emblem, a baseball framed in a ship's wheel with captain's wings sticking out the sides. Gold piping and stripes trimmed out the rest of the outfit, which almost certainly wounded team morale.

After a tough 8-17 start, the Pilots climbed into a somewhat respectable third-place position in the AL West and held it into August. Then some weak pitching and a rash of injuries led to a 2-18 slide, quickly sinking the Pilots into last place, where they would finish the season. What proved to be the Pilots' final game on October 2, a home loss to Oakland before a typically paltry 5,473, left them with a final record of 64 wins and 98 losses, 33 games behind the first-place Minnesota Twins. As a team they batted an anemic .234 and scored only 639 runs, while their opponents racked up nearly 800. The pitching staff's combined ERA of 4.35 and the defense's 167 errors were both league-worsts. At season's end, skipper Joe Schultz and his coaching staff were all fired.

The Pilots' on-field buffoonery certainly didn't help attendance, but Seattle, one of the smaller major league markets, was itself in an economic slump. The Pilots needed a turnout of 850,000 to break even on the year, but only 677,944 passed through the turnstiles, an average of 8,340 per game. The ticket and concession prices were among baseball's highest, alienating many potential fans. Not once did Sick's sell out; the largest-ever crowd was 23,657 on August 3 -- Bat Day -- versus the New York Yankees.

All things considered, it was doubtful the Pilots would remain in Seattle for a second season. Off the field, the organization was marred by mess of arguments and lawsuits and other problems. The team had little hometown exposure as it was unable to negotiate a local TV contract. Stupid trades were made. In September, Seattle mayor Floyd Miller tried to evict the team from Sick's, even though several home games remained in the season. The owners blamed the people of Seattle for not supporting the team, but with all the above problems, they could hardly have been expected to. For obvious reasons, the inexperienced ownership duo of William Daley and Dewey Soriano sought to sell off the floundering franchise, which initially cost them $6 million. No reputable local buyers could be found, but a group of Wisconsin businessmen offered $10.8 million to woo the Pilots to Milwaukee, a city smarting after losing their Braves to Atlanta in 1966. Citizens' groups took desperate measures to prevent a move, to no avail. Near the end of the tumultuous off-season, the Pilot owners had no choice but to declare bankruptcy. The American League approved the sale to Milwaukee on March 30, 1970, just one week before the start of the new campaign. The Pilots consequently earned the distinction of being the only team in Major League history to go bankrupt, and the move marked the only time since 1902 that any city lost their franchise after just one season.

As the team wrapped up spring training in Arizona, their uniforms were altered at the last minute by switching the "S" initial on the caps to an "M," and changing the nicknames on the jerseys to "Brewers." When the Brewers began play in Milwaukee on Opening Day 1970, a booth was set up outside Sick's to sell off leftover Pilot memorabilia. T-shirts, pennants, yearbooks, and bobbing head dolls were priced to move. The Brewers have remained mostly happy in Milwaukee ever since, even though the team seems to be in denial about their team's inauspicious origins.

Besides the Brewers, the Pilots' only other lasting contribution to baseball was the controversial bestseller Ball Four, written by goofball relief pitcher Jim Bouton. The no-holds-barred journal of his days with the Pilots raised hackles for a variety of reasons, including his harsh criticism of team owners and frank talk about players' alcohol and amphetamine use. The book also addressed racism in baseball, juvenile clubhouse hi-jinx, and "beaver shooting." Bouton's unapologetic, taboo-breaking account shattered the public perception of ballplayers-as-heroes, instead revealing them to be everyday guys. Ball Four outraged the baseball establishment and made Bouton many enemies, if only because his warts-and-all account was unflatteringly honest. On scary-looking pitching coach Sal Maglie: "(He) looks like Snoopy doing the vulture bit." On Seattle: "A city that seems to care more for its art museums than its ballpark can't be all bad." On the team's attire: "I guess because we're the Pilots we have to have captain's uniforms... We look like goddamn clowns."

Some Seattle fans were relieved to see the troubled Pilots set sail while others felt the team had been stolen from them, but all would welcome baseball's return to town seven years later. Under threat of lawsuits against the American League, Seattle interests were assured that upon the next expansion they would get a new team. In 1977, the Mariners began play in the Kingdome, the new multi-purpose stadium approved by King County voters in 1968. Former Pilot Diego Segui was the Mariners' starting pitcher for the home opener, the only guy to ever play for both Seattle franchises (and also whom David Letterman once claimed was his all-time favorite ballplayer). The Mariners' presence almost instantly erased Seattle's foul memories of the Pilots, even if their maiden campaign's record was an identically lousy 64-98. In their first two decades, the M's generally upheld the Pilots' precedent of chaos and futility, at least until the mid-'90s, when they finally became contenders under feisty manager Lou Piniella. Incidentally, Piniella was a promising young prospect drafted by the Pilots, but was foolishly sent packing to Kansas City just before the '69 season started. There he would earn Rookie of the Year honors.

The unsightly Kingdome was demolished in March of 2000, shortly after Safeco Field opened, though Sick's Stadium had already been pummeled by a wrecking ball in 1979. Today on the site stands a giant Lowe's Home Improvement warehouse store. On the sidewalk outside the exit doors is a home plate, affixed to the spot where the actual Sick's dish once lay. Inside the doors stands a small display case filled with Sick's-era photos and other memorabilia. The majority of Rainier artifacts compared to just two Pilots items -- a cap and a schedule -- is indicative of how beloved the Rainiers still are, whereas the dreadful Pilots are mostly forgotten. Moreover, on the street corner outside Lowe's is a small wooden sign, erected by the city, which doesn't mention the Pilots at all. It reads in its entirety, "Historic Site of Sick's Stadium, 1938-1979, Home of the Seattle Rainiers Baseball Club."

Seattle Pilots, we hardly knew ye.

Different versions of this article have appeared in Heinous, Slant, ChinMusic! and The Grand Salami.

Back to Top

|